The Antichrist, or Dajjal, is not merely a future individual. He is a recurring phenomenon: a corruption that arises when religious authority is wielded without accountability, when God’s message is twisted into an instrument of control. The Qur’an repeatedly warns against this distortion—not from enemies of faith, but from within.

Surah Al-Hadid, verse 25 presents a powerful metaphor:

“Indeed, We sent Our messengers with clear proofs, and We sent down with them the Scripture and the Balance so that the people may uphold justice. And We sent down iron, in which is strong force and benefits for people…” (57:25)

Here, the Qur’an, which is the Balance, and iron are all described as tools—each serving the aim of justice. Scripture conveys moral truth. The Balance allows discernment. Iron represents tangible force. But none of these are good or evil in themselves. They derive their moral character from how they are used.

Iron can support or destroy. It forges surgical instruments that save lives, yet also the chains of slavery and weapons of tyranny. In the same way, scripture—pure in origin—can become a tool of corruption when interpreted through arrogance, ignorance, or the thirst for domination. When scripture is used to micromanage, to control, to declare war on nuance and inquiry, it ceases to liberate and begins to enslave.

This is why the Qur’an explicitly forbids theological overreach. Surah Al-A’raf, verse 33 declares:

“Say, My Lord has only forbidden indecencies—open and hidden—sin, unjust aggression, associating partners with Allah for which He has sent no authority, and to say about Allah that which you do not know.” (7:33)

To label something haram without divine evidence is to speak on behalf of God without knowledge—an act considered spiritually criminal in the Qur’an. As Javed Ahmed Ghamidi consistently argues, only that which is clearly prohibited by Allah and His Messenger can be rendered impermissible. Anything else falls into the realm of human judgment—not divine decree.

Modern Salafism and the Illusion of Orthodoxy

Many contemporary Salafi scholars claim orthodoxy by narrowing the scope of legitimate opinion, branding dissent as deviation. But Islamic tradition is not a monolith. Across the centuries, jurists have disagreed—even on matters modern-day Salafis claim are settled.

Consider the following examples:

Shaving the Beard: Imam al-Shafi’i did not regard shaving the beard as haram. He considered growing the beard part of ‘urf (cultural practice) and did not impose legal rulings upon it. The insistence by some Salafi circles that shaving the beard is a major sin reflects an absolutism alien to Shafi’i’s jurisprudence. Source: Al-Umm by al-Shafi’i; also discussed in al-Nawawi’s Sharh al-Muhadhdhab

Music: Ibn Hazm also allowed music, arguing that the ahadith used to prohibit it were either weak or misinterpreted. He insisted that singing and musical instruments are not inherently sinful unless associated with immoral behavior. Source: Ibn Hazm, Al-Muhalla, Vol. 7, Issue 694

Alcohol Without Intoxication: Abu Hanifa permitted the consumption of fermented drinks like nabidh as long as they did not intoxicate. His position relied on the linguistic scope of khamr and the Qur’an’s emphasis on intoxication as the cause of prohibition. Source: Al-Hidayah by al-Marghinani; Bada’i’ al-Sana’i’ by al-Kasani

Prayer in Persian: Abu Hanifa initially allowed new Muslims to pray in Persian until they could learn Arabic, prioritizing understanding over formality. His view was later modified by his students, but it reflects the Hanafi commitment to maqsad (purpose) over form. Source: Al-Mabsut by al-Sarakhsi, Vol. 1, p. 15

N.B.

The author neither agrees nor disagrees with the above rulings

Scripture Demands Reverence—and Openness

To interpret scripture is not to dominate it, but to submit to it. The Qur’an must be treated as the speech of God—not a weapon of men. It demands humility, not dogmatism; deliberation, not instant verdicts. Reverence is not silence—it is the courage to understand. It is to allow the text to speak through language, reason, and context, rather than through preloaded ideology.

As Ghamidi reminds us, Islam is not a prison of ritual legalism. It is a message meant to be understood. When we approach the Qur’an with open minds—minds willing to weigh, to reflect, to admit uncertainty—we treat the Book with the dignity it deserves. To do otherwise is not caution. It is betrayal.

“And the Messenger will say, ‘O my Lord, my people have taken this Qur’an as a thing abandoned.’ (25:30)

Abandoning the Qur’an is not merely to leave its recitation. It is also to mute its meanings under the weight of inherited rigidity. It is to cite it without understanding it. It is to claim its authority without submitting to its method.

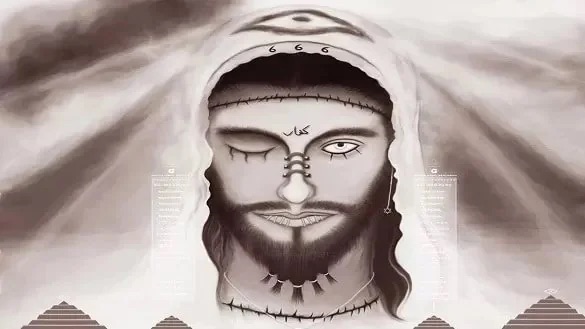

Conclusion: The Mask of the Antichrist

The Antichrist in religious people is the one who replaces God’s mercy with his own authority, who shuts the door of ijtihad (personal religious reasoning) and labels dissenting voices as deviant. He does not deny the Qur’an—he monopolizes its interpretation. He praises the early generations but cherry-picks their opinions, erasing the diversity that once defined Islam.

The Qur’an and iron were both sent to establish justice, not domination. We must guard against those who turn divine guidance into a tool of fear. As Ghamidi insists, the religion of God is simple, principled, and open to reasoning. Its purpose is liberation, not legalism.

The Antichrist will always wear the cloak of religion. But he will never speak with the voice of God.

Leave a comment