The very fact that you exist means that you must make choices. It is unavoidable. To be human is to decide. Almost tragically, even the refusal to choose is itself a choice—a surrender to drift. One may choose to heal or to harm, to wander aimlessly or to move with purpose, to waste the hours or to sanctify them. Every breath carves a path. The question is never if we will choose, but what we will choose

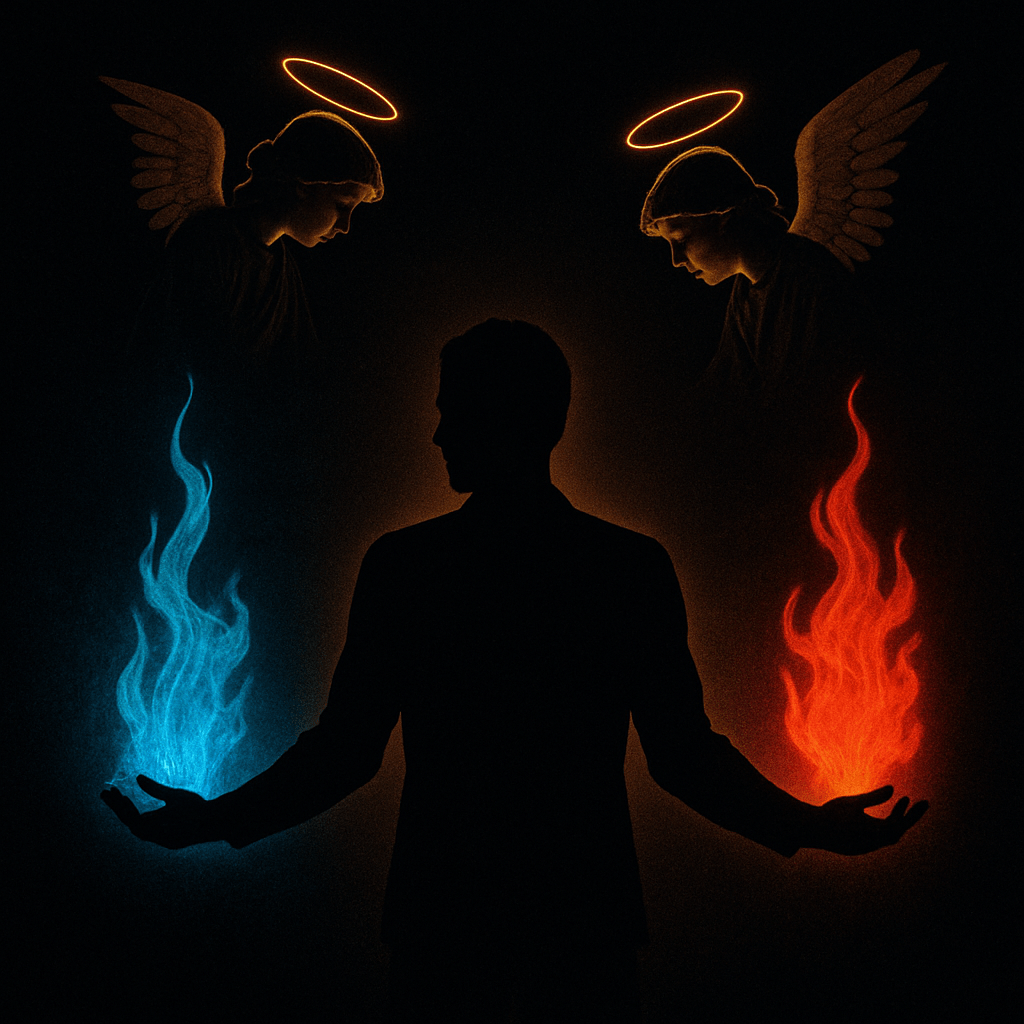

Freewill is the most exquisite and dangerous gift given to human beings. It is a dual-edged blade: the very power that allows us to rise to virtue also enables us to plunge into ruin. Without it, life would be nothing but a pre-written script; with it, every choice becomes a battlefield of meaning.

This gift is not an accident of nature—it is a trust (amānah) given to us by God. Pause and reflect: though the freedom of choice may feel burdensome, would any of us truly give it up? Would we prefer to be lifeless rocks, thrown around and crushed without say, or trees, rooted in one place for centuries only to be cut and turned into furniture? The possibility of choice is what separates existence from mere survival. It was through God’s rūḥ breathed into us that we obtained it, and it is by His command that we can return to our most natural, peaceful selves.

Yet the blade cuts both ways. Freewill can be used to build cathedrals of justice, to write poetry, to give mercy when vengeance is deserved. But it can also be turned inward, slicing into our own integrity. We wield it poorly when we confuse freedom with indulgence, or when choice becomes a mask for compulsion.

The main reflexive and transitive harms of freewill lie in ego and lust.

Ego (Latin ego, “I”) harms the self by trapping us in pride and self-delusion, but it also harms others by bending relationships around domination. It makes every bond transactional, every encounter a stage for the self to shine. What begins as an inward inflation becomes an outward suffocation.

Lust (Old English lust, “desire, pleasure”) likewise consumes both self and world. Reflexively, it enslaves the soul to appetite, chaining will to fleeting sensation. Transitively, it reduces others into objects of gratification, stripping them of dignity. What was meant as a spark of intimacy and creativity becomes a fire of exploitation.

This is why submission (islām) is the path to purity. By yielding parts of our ego and lust to God—by recognising His wisdom over our own impulses—we do not lose freedom, we perfect it. He knows the being He created better than we know ourselves:

“Does He who created not know, while He is the Subtle, the All-Aware?” [Al-Mulk:14]

True freedom is not the absence of limits, but the mastery of them under the One who set them. Freewill is not an endless buffet of options; it is the responsibility of steering the self with precision, discipline, and trust. The double-edge remains, but so too does the possibility of balance.

The question is not whether we have freewill—it is whether we will entrust it back to the One who gave it.

Leave a comment